Advancing Neighborhood Commercial Corridors

By Bruce Katz, Elijah Davis and Anne Bovaird Nevins

Over the past several years, this platform has returned multiple times to a geography found in cities of all sizes across the country – the neighborhood commercial corridor. With many others, we documented the harsh effects of the pandemic on neighborhood serving and locally owned businesses and offered practical recommendations for local stakeholders and state policymakers alike. To the greatest extent practicable, we have tried to be grounded and granular: using Investment Playbooks to identify concrete and fundable projects that can drive a burst of inclusive growth and entrepreneurship in real places, most recently 52nd Street in West Philadelphia.

Our hypothesis is straightforward: the inclusive revival of commercial corridors in low-income communities presents a clear test for a federal government and many financial institutions, corporations, and philanthropies that have committed to racial equity as a central component of the post pandemic economy.

These business districts are the front doors to low-income communities. When vibrant, they offer neighborhood residents walking and transit access to business and employment opportunities, social services and gathering places. When well-designed and maintained, they create a distinctive quality of place and reinforce a sense of community. Inclusive regeneration strategies can both serve community residents with the high quality and affordable goods and services they require and fuel the growth of local Black-and-Brown-owned enterprises they demand.

With trillions of dollars in federal funds flowing, these small but dense geographies tell us at a glance whether the lives of city residents have been improved or changed for the better. This assessment does not require deep statistical analysis; it can be garnered in less than an hour by walking the streets, talking to business owners, employees, and residents, and taking in the collective sense of the place.

In May, following The Enterprise Center’s grand opening of their new Community Resource Center on 52nd Street, constructed entirely by minority contractors, Drexel University’s Nowak Metro Finance Lab and Accelerator for America convened a regional and national group of community intermediaries, financial institutions, and philanthropies in West Philadelphia. Our goal: share promising practices, ask challenging questions, and identify potential new models to advance more equitable and sustainable corridor development for communities across the country.

In this piece, we zoom out from West Philadelphia to take account of broader dynamics that now affect these corridors, highlight some promising initiatives underway around the country, provide an overview of early lessons from Detroit, and then propose next steps to blend new federal funding and mission-driven private and civic capital to drive inclusive regeneration.

Trends in the field

Market trends

Several post-pandemic dynamics shape the development and financing landscape for commercial corridors.

First, traditional consumption and employment patterns continue to shift. Many commercial corridors in cities have never recovered from the emergence of suburban shopping malls and big box retailers. In the past decade, e-commerce sales have more than doubled, representing a change in retail shopping patterns via the on-demand economy. At the same time, the stickiness of remote and hybrid work arrangements for white-collar workers accelerated during the pandemic. This has precipitated enormous challenges for central business districts, municipal tax revenues and transit ridership but potentially created new market opportunities for neighborhood commercial corridors.

Second, parasitic corporate institutional investment in low-wealth Black and Brown neighborhoods is accelerating post pandemic. On the housing side, our work shows that these investments (Investor Home Purchases and the Rising Threat to Owners and Renters: Tales from 3 Cities) have disrupted residential markets, which could affect the local consumer base of corridors. On the commercial side, dollar stores are crowding out premium chains and local entrepreneurs while constricting the quality and variety of commodities available in neighborhoods.

Third, we are in a historic moment of federal, corporate, and philanthropic investment. Together, the American Rescue Plan Act, the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act make up a package of $3.9 trillion of federal investment that, if implemented well, could present a unique opportunity for place-based initiatives. These resources are unprecedented but not explicitly targeted to the regeneration of commercial corridors. While the CARES Act and ARPA initially enabled flexible recovery resources to be invested in commercial corridors, subsequent federal investments do not prioritize these geographies or the investments likely to fuel an inclusive recovery. We need to invent a new norm that also brings in private investment and philanthropic funding if federal infrastructure and other investments are to be leveraged and channeled. To that end, the formation in July 2022 of an Economic Opportunity Coalition of major financial institutions, corporations, and foundations creates a national platform for new commitments, transparency, and accountability.

Development Trends

Against this market backdrop, corridor managers, developers and nonprofit intermediaries have been experimenting with new approaches to and vehicles for corridor development.

Ownership and governance: As LISC, Brookings and Next City have chronicled, models and initiatives for community ownership of commercial properties are on the rise, such as Portland’s Community Investment Trust, Philadelphia’s Kensington Corridor Trust and We The People in Chicago.

Developer Diversification: After site control comes development, but, as the New York Times reported in March, of 383 top-tier developers that generate more than $50 million in revenue annually, one is Latino; none are Black, offering limited opportunity for development to catalyze wealth building. Responding to this disparity, multiple minority developer accelerator programs are underway in places like Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Philadelphia. Increasingly, these programs are being designed to recognize the importance of combining land acquisition opportunities, customized advisory services, mentorship and peer learning, and capital access, including for acquisition and predevelopment.

Innovative Capital Products: New funds for commercial development and ownership are also being piloted, such as predevelopment funds from CDFIs and special purpose credit programs from banks. New sources of place-based capital are being structured and deployed, such as the Community Foundation for Greater Atlanta’s GoATL Economic Inclusion Fund to support underserved and BIPOC entrepreneurs.

Business support: A surge in small business support services have taken hold with newer, corporate stakeholders, such as Mastercard’s STRIVE city initiative, designed to bring digital resources and expertise to main street businesses in communities like Birmingham and St. Louis. In San Antonio, the city is piloting a commercial corridor capacity building program with Main Street America. Yet, the availability and connection of high-quality and affordable professional advisory services for low-wealth entrepreneurs, such as legal assistance for lease negotiations or industry-specific financial and accounting services, has not been solved at scale.

Experimental uses and forms: The very form of development is changing as well. While density along corridors is still desired, the future of corridors is mixed-use. At the same time, pedestrian-scale retail and office tenants are experimenting with new configurations of square footage that are omnichannel and serve the experience. Banks, usually late-adopters to innovations in urban design, have begun trialing “third place” cafés within their retail branches, which might otherwise struggle as traditional branches as foot traffic declines nationally.

New public-led initiatives: In the past four years, cities have been early movers in rethinking commercial corridor development and organizing corporate and philanthropic commitment differently. Buffalo’s East Side Avenues Initiative, Chicago’s INVEST SOUTH / WEST and Charlotte’s Corridors of Opportunity are all in the new vanguard of commercial corridor development. ARPA also spawned numerous small business relief programs focused on commercial corridors, such as St. Louis Development Corporation’s (SLDC) North St. Louis Commercial Corridor Revitalization Program and the City of Dayton’s First Floor Fund.

Building on the above innovations, the regeneration of today’s commercial corridors will require even more radical interventions, including new financing approaches focused on co-invested funds with new term sheets, direct investments, and capacity-adding expertise. An emerging model for this is Detroit’s Strategic Neighborhood Fund, which we believe could be adapted or adopted in communities nationally.

Detroit, a first mover

In Detroit, more than $185 million in investment from 24 funders is being deployed in 10 neighborhoods through its Strategic Neighborhood Fund (SNF), a partnership between the City of Detroit and Invest Detroit, a CDFI. Beginning in 2016, first deployed in 2017, and expanded to a second round in 2018, the City of Detroit and Invest Detroit began the program to ensure that the revitalization seen in the city’s downtown extended to neighborhoods across the city. SNF’s underlying thesis is that a whole-of-neighborhood approach needs operational and financial synergies with concurrent investments in infrastructure, housing, and mixed-use development.

Now eight years in existence, the program currently serves 10 neighborhoods, up from three at the inception. JP Morgan Chase is one of the leading philanthropic and patient capital investors in the effort and has invested a total of $10 million directly into the fund. SNF’s core notion is the “20-minute neighborhood”, a variant of the 15-minute city, the idea that residents, regardless of socioeconomic station, can access needs and wants within a 20-minute walk or ride from their home.

While many of the projects are under construction and the program is still in its early execution stages, there are early signals of its impact. According to a University of Michigan sentiment study of SNF 1.0 in 2019, residents of the first three communities that saw investment reported an increase in their overall quality of life and neighborhood satisfaction. Additionally, residents did not feel an additional risk of displacement.

Demographic indicators also signal growth, where the population has increased in six out of 10 neighborhoods and residential vacancies have decreased in nine. Incomes have increased in all the neighborhoods except one, and the poverty rate has decreased in all target neighborhoods. Invest Detroit COO Carrie Lewand-Monroe also remarks that SNF’s strategy of deploying dollars for market-rate housing and affordable housing both ensures growth and guards against displacement.

What we learn from the Strategic Neighborhood Fund (SNF)

The Detroit Strategic Neighborhood Fund is a multigenerational program that merits a longitudinal impact study, but there are early insights from their model that cities can begin mirroring now with their development ecosystem for neighborhood commercial corridors.

1. The importance of a sophisticated CDFI with a product-market thesis

Source: invest Detroit

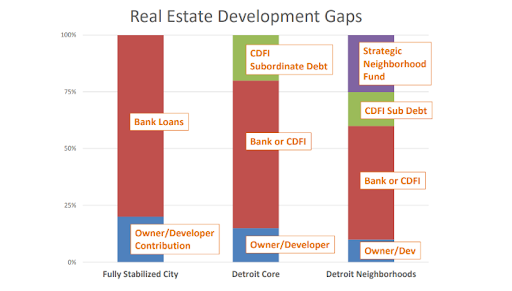

Invest Detroit developed a market thesis for their products by assessing the coverage of products currently in the marketplace. They reasoned that in neighborhoods with depressed property values, lower wealth profiles, and weaker consumer demand there needed to be another layer of concessionary capital that “filled the gap” left by owner equity, banks and CDFIs. Their approach is to be the chief dealmaker, arranging capital for some deals, providing capital in most, and pledging equity in special cases.

2. The possibility for multi-sector, flexible capital at scale for neighborhood development

Source: Invest Detroit

With the City of Detroit accounting for more than half of the program funding, SNF has marshaled 24 funders including corporate philanthropies and foundations. $110 million in public resources has been matched by $75 million in philanthropic resources. The SNF funds have catalyzed additional sources of capital to be invested. All told, $262 million has been deployed, $140 million of which has been invested for commercial uses including but not limited to small business loans and mixed-use developments. For corridor redevelopment, the impact of flexible, pooled capital allows for product differentiation and later, innovation. Scaled capital also allows for underinvested neighborhoods to build high-quality and accessible amenities for existing and new residents through concurrent investment and projects in parks, streetscape, mixed-use developments.

3. The need for cross-functional teams to synergize and maximize development efforts

Source: Invest Detroit

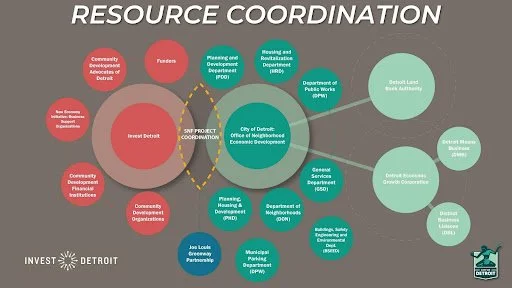

SNF’s pooled investment is not only financial capital, but also pooled human capital. Nine city departments and four partner agencies convene weekly to discuss projects. Rather than relegate projects to a siloed periphery, projects are stewarded and kept in clear focus with the buy-in of city officials and key partners. Wide ranging city departments from planning to general services, to housing, and agencies like the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation (DEGC) collaborate to ensure that projects move from concept to fruition in an efficient and expeditious manner.

With a pooled fund, all funders technically see their dollars go to all neighborhoods. SNF’s partnership approach gives a company a geographic place where they are also publicly celebrated in wins and where they might align additional investment above and beyond SNF (including non-cash activity such as volunteerism).

An emblem of the fund’s impact has been the development along the Livernois-McNichols corridor. Known as the “Avenue of Fashion,” Livernois is a historic African-American cultural district near major anchor institutions like the Marygrove Conservancy, itself a $57.3 million redevelopment. The corridor has received adjoining commercial and infrastructure investments that have sped up the rate of visible transformation. One sign of renewal with direct local benefit is the Detroit Pizza Bar, a Black-owned restaurant which received $550,000 in SNF investment plus a $1 million allocation in New Market Tax Credits creating 20 jobs, with 97% of the jobs coming from a two-mile radius. In the same catchment area, SNF also contributed financing to the planning of Sawyer Art Apartments, a $10.8 million mixed-use development led by a Black development team, scheduled for completion in 2024.

The early lessons from Detroit demonstrate the power of public-public and public-private partnerships. They deploy catalytic capital, cross-functional teams, and cross-sector collaboration in unique ways. As efforts mature, it will be important to distill the features from other first mover cities and chronicle lessons learned. Now that federal funds are being clarified, and groups like the Economic Opportunity Coalition are sharpening their focus, new resources could expand the tools of community development finance. The Economic Opportunity Coalition, for example, recently announced that it reached $1 billion of investment into minority deposit institutions (MDIs) and CDFIs. As we wrote in June in our interview with Arctaris, and as we learn from Fifth Third’s Empowering Black Futures Program (Fifth Third Neighborhood Investment Program), a financial institution’s adaptation of SNF, the rise of funds that are “place-based and not product-based,” may be the new vehicle for neighborhood regeneration.

Next Steps

As we reflect on insights from Detroit, there is a lot to learn and do to meet the moment for commercial corridor investment. As the capital environment moves from relief to resiliency, we should take inspiration from Detroit itself, reinventing its economic identity within 10 years of the city government filing for bankruptcy. Similarly, the post-pandemic moment of economic transition should allow us to create new approaches and blended financial products. To advance this work, we propose the following next steps:

Work with a coalition of banks and impact investors to invent and introduce a new generation of routinized financial products for neighborhood commercial renovation and acquisition that account for individual wealth, property valuation and organizational asset disparities. Particularly, pilot a national commercial acquisition fund for commercial corridors in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color that directly addresses the wealth gap.

Work with banks, philanthropy, and the public sector to find more flexible low-cost capital to channel through CDFIs to continue the momentum we are seeing in inclusive growth strategies across the country. As banks continue to avoid projects and businesses perceived as higher-risk, CDFIs have seen demand for their products skyrocket. This additional demand has not seen a commensurate increase in supply of low-cost capital to the CDFIs, paired with operating grants to ensure that they have capacity to expand their outreach and services.

Identify the parts of the Detroit SNF model that are transferrable and replicate elsewhere to “fill the gap” of projects to get them off the drawing board and into the ground. In Detroit, the gap was approximately 25-40% of the project cost; historically, city leaders have grappled with capital stack gaps of 8% to 50% depending on the project’s sources and uses. Local government and philanthropy can mirror Detroit’s success to ensure that these projects get built.

Capitalize on the advent of the Thriving Communities Network and Interagency Community Investment Committee and continue ARPA’s momentum of commercial corridor resources by designing a reform to the Community Development Block Grant, Choice Neighborhoods, Opportunity Zones, and HUB Zones to expand eligible uses and funding for economic development activities and capacity building on corridors within these geographies.

Work with the Small Business Administration to modernize the 504 Loan Program which is typically used for the renovation of commercial property. Currently, Black and Latino borrowers combine for just over 13% of the value of SBA 504 Loans.

Conclusion

As cities grapple with inclusive recovery strategies following the pandemic, neighborhood commercial corridors have escalated in importance as key indicators for neighborhood health, job access and small business equity. The next generation of corridor regeneration will necessitate that urban jurisdictions properly coordinate the influx of federal funding, direct new types of flexible investments from corporate and philanthropic investors, and empower municipalities to lead with better data and zoning instruments. In the next decade, commercial corridors, with the right strategy, partnership, and financing, can be restored activity centers and realize their potential as the physical, cultural, and economic hearts of communities.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Elijah Davis is a Research Officer at the Nowak Lab. Anne Bovaird Nevins is the Director of Economic Development for Accelerator for America.